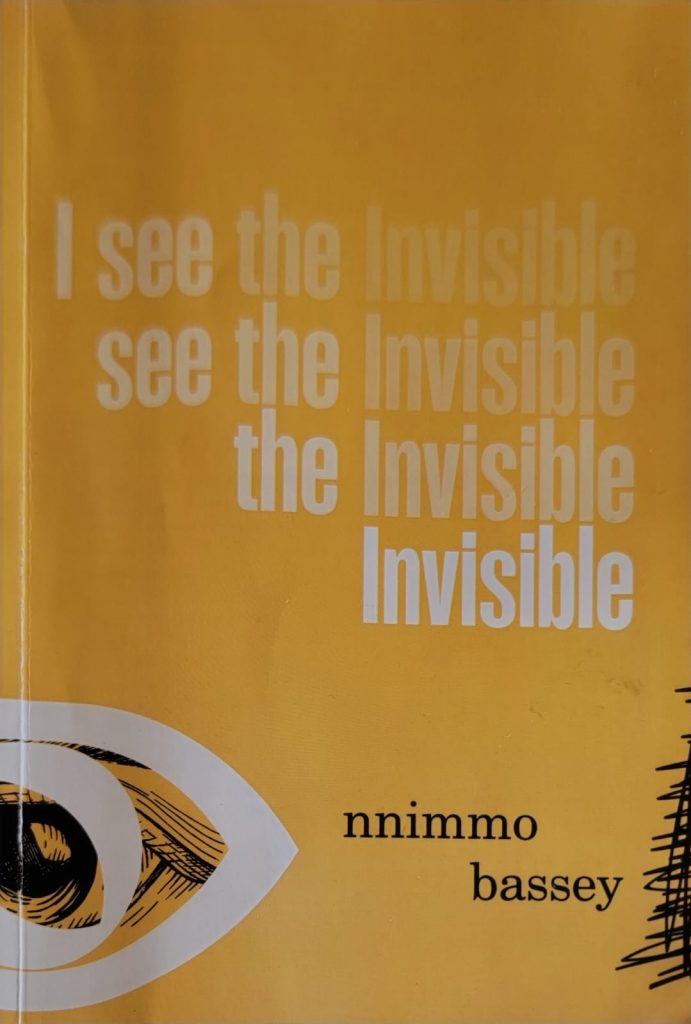

Kufre Friesenhan: Congratulations on the new poetry collection. I was so very excited when I saw your announcement on Instagram and could not wait to read the work. How does it feel to birth a new child so to speak, after some time away?

Nnimmo Bassey: It feels like having a baby long after you have hung the boots and thrown in the towel. A huge pleasure, I must say.

K.F. I really admire your coherence in constructing the poems in I See The Invisible. The sections are so cohesive; they all fit together like a puzzle, making this collection different from the previous ones. I see The Invisible moves in a different vein and I enjoyed that. How do you collate the poems in each collection?

Nnimmo Bassey: Each poem had to echo the tone of the community or section they found themselves in. The entire collection was conceived as having a common DNA, but the poems were not written with sectional divides in mind. They simply found their ways to get connected to their kin. Kinship is the common thread that wove them into the families.

K.F. And speaking of kinship, I like the kinship thread woven throughout the collection and the moves you make to foreground our shared vulnerability with the nonhuman. could you share more about kinship and its place in our world in a time of climate crisis?

Nnimmo Bassey: All beings are one despite our closer affinities to our kind. we are woven in a beautiful rainbow net. These family members are all around us and in us. They are both visible and invisible. We cannot do without them, we cannot do without them, but they may arguably do without us. Our kins are intricately and inseparably connected in this web. Our resilience is in our multiplicity, and that multiplicity reinforces our broken unity. Although this is continually challenged by our predatory inclination. The climate crisis wakes us up to the fact of the delicate balance configured in the universe of our being and the disruptions of one habitat, or even nourishment, destabilize the natural flows, cycles, and balanced spatial spread. This balance must be restored. The cycles must be secured. Our kinship keeps us within the pull of gravity. Broken, we splinter and fly away. And that’s where the burning up occurs, while we think we are merely warming.

K.F. Your history as an environmental activist seeking justice for Indigenous peoples of the Niger Delta is reflected in the poems in this collection. There’s a way in which you brilliantly connect the communal or the personal with the universal. Do you see connections between the environmental work you do worldwide and your work as a poet? What does it avail or foreclose?

Nnimmo Bassey: There is an absolute link between my poetry and activism. It can be disturbing at times, but poetry is an invaluable cultural tools that recall songs that accompany individual and communal labours in our communities. That said, I must say that my activism may have affected my creative endeavours because our fights are about life or death and the vampires we confront are so ruthless in their socioecological misbehaviours. Some people may consider poetry as an escape route, but for me, it is the visionary goggle for pinpointing the adversary, and the gongs for calling the oppressed to battle. No room for romanticism. Every line is a red line on the sand.

K.F. When I flipped through I See the Invisible, I first noticed that the poems are often long and thick with words. Poetry is often linked to the brevity of words, but you have a lot to say to the reader. Why is that? And how did that formal decision evolve?

Nnimmo Bassey: I have wondered about that, too. This pattern emerged because one had to get true to the pull. One had to take the space, while still leaving room for readers to read between the lines. Don’t forget that there are more than 250 languages in Nigeria. That tells me we have a lot to say and should not shy away from letting the words out and creating new languages if the present ones are inadequate.

K.F. I fear the grassroots is our last resistance to neocapitalism in its myriad forms. Tell us about your work with HOMEF and grassroots organizing.

Nnimmo Basssey: You are right. Capitalism and all its manifestations will not be overthrown using the same instruments and imaginaries that erected and sustained it. It doesn’t take prisoners. It will take the globalization of the grassroots and their power to present humans and other than humans a fighting chance to survive and thrive. This is why in HOMEF we strive to expose the roots of our multiple malaise, be embedded in our communities and deeply learn from our people.

K.F. Finally, has your polemical stance concerning hyper-extraction changed? Do you still believe the oil should remain in the ground?

Nnimmo Bassey: Leaving the oil in the soil is common sense. It is the ultimate solution to the polycrisis. The petroleum civilization must come to an end. It is time to depetrolize, not merely decarbonize. We can make the needed energy transition without replicating the colonial, extractivist and harmful modes of the present dirty energy mode.

K.F. What an insightful chat. Thank you for sharing your time and thoughts with us.

Add comment